Enrique Soto

Salta, Argentina

Woodworker, crafts artisan

Enrique’s woodshed is a holy place. Huge tree trunks twist and reach for the ceiling in the corners of the room; boxes of discarded figurines — one-legged llamas, headless saints, wingless birds — are strewn randomly across the floor; sawdust layers the ground like Malibu sand. Old tools line every inch of every wall, soldiers poised for battle.

With the exception of two large machines — a precision cutter and a sander — the place is devoid of any modern indication. But even these are coated with rust, hand-powered relics of high technology in the 1920’s. A long line of cubbies snakes across the tin roof, each holding some unique trinket or half-completed project from years past.

It is utterly chaotic, and utterly beautiful.

The space, nestled between overgrown shrubs behind Enrique’s mother’s house, is truly that of a workman, and I’m fortunate to have been welcomed here. While browsing the mercado artesanal in a rural outcropping in Salta, Argentina, a store owner’s interest in my instruments sparked a long conversation that ended with an invitation into her home (Argentinians can be like this). Before I knew what had happened, I was sitting at this woman’s dining room table playing music with her son, and being served freshly grilled asado.

Her son, Enrique, hand-crafts artesanal goods in this backyard woodshop, which are, in turn, sold at his mother’s shop. It’s a family business, and the Sotos have a long legacy of artistic contribution: his mother is an amazing painter, his uncles are metal workers, glass blowers, and carpenters, and his grandmother was a doll-maker. His grandfather built the house 70 years ago with his bare hands, and the Sotos have lived there since.

Entering the shack, I feel aucasinosonline.com/sa/ a magical air; it is as if time has swept through kindly and passively, leaving the core elements of fabrication unmarked. Enrique had spent hours hunched over in here, working until 4 in the morning, lost in an inventive fervor, just as his grandfather had.

As I stand in the sawdust, I realize something very, very important: no matter what happens in my life, I must never lose the feverish passion, the creative spirit — my equivalents of Enrique’s obsession.

I mill around and watch Enrique violently sand down a llama-shaped salad mixer for a while as Salteno music tweets faintly from a battered boombox. These llamas are a best-seller at his mother’s shop, and he has a high stack of them that have yet to be completed, so I offer a hand. We work side by side: I, using a hand crank to drill eye holes, and he meticulously measuring out inlays of exotic woods — negra, rosa, ebony, all in beautiful tri-tonal shades. He tells me, as he labors away with a rusty handsaw, that he once used to make everything strictly by hand, but that he simply could not keep up with the demand; he seems nostalgic telling me this, and glances resentfully at the large sanding machine.

…

I worked here for a week, in this small, hot, beautiful shack, sleeping nights in a spare bedroom full of sheep hides and clumps of wool. On the last day, as I gather my things, Enrique hands me a small gift wrapped in newspaper before disappearing into the shack to finish the day’s work.

I catch a bus to Cachi, an isolated mountain town, and rock-hop up the side of a hill in the twilight, thinking that I’ve learned more about life in that shack than I could’ve from 20 years of schooling. I gently fold the newspaper back to reveal a carved figurine of the patron saint of Salta.

I’d found her buried deep in one of the discarded boxes, mingling with the one-winged birds and the scarred caballos who’d never made it onto mantles or display shelves. She had chipped away a bit at the feet, and stood lopsided on an even surface, but never seemed to surrender to gravity. She maintained pride despite her ailments, her hardships, her pain.

All is quiet and calm; the few lights below have faded, and even the dogs have retired from chasing mariposas. Sitting on this hill, we watch far-off lightning disrupt the purple sky.

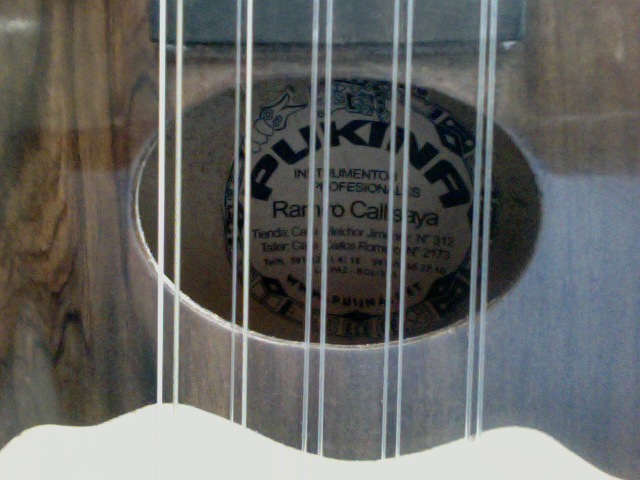

Ramiro Callisaya

La Paz, Bolivia

Luthier, traditional Bolivian instruments

Ramiro and I met during a time of desperation.

I had just come from Potosi, a small mining town where had been bit by a rabid street dog. I subsequently took a 14-hour overnight bus to La Paz and spent two days desperately searching for a reliable rabies vaccination to prevent my inevitable, excruciating death.

Under a relentlessly brutal sun, and trapped in the street traffic of a Sunday marketplace, I was comforted by the mystical tinkling of far-off strings. Between the shrill whistles of street vendors and the undulating hum of toxic combis, I wasn’t sure at first if what I was hearing could be trusted. But stepping aside and wandering down a cobble-stoned alley, I could hear the noise more distinctly. So, I followed it like a charmed snake, slithering past boarded doors and jangling cups of coins.

Then I saw him: a dark figure hunched in an unlit shop, the 12-stringed neck of an unknown instrument jutting out with his shadow like a third arm. The jangling strings reminded me at once of my journey through the mystical mountains of Peru; I could almost taste the fresh air of the Cordillera Blanca.

This was Ramiro’s creative space: a small, dusty enclave in the witch district of La Paz. In a rapidly-modernizing industrial city, surrounded my mobile phone stores and internet cafes, this man unlocked his door every morning at 6 AM, hobbled to his work bench, and constructed the most beautiful hand-crafted instruments I’d ever seen. A look around the pock-marked concrete walls was all I needed to verify his expertise and passion.

I’d seen many charangos on my trip, but none like these. As a musician and instrument collector, I felt I’d stumbled across the Holy Grail: exquisitely hand-carved necks, immaculately inlayed armadillo shell bodies, seamless integration of native woods.

I timidly approached, and for an instant saw him working without knowledge of my presence. He hovered above the fretboard of a newly crafted ronroco, gently shaving away peels of ebony which spiraled downward like winged conifer seeds. A small work light illuminated a forehead wrinkled with concentration and intensity. I immediately connected with this man and understood his devotion to artistry.

…

When we got to talking, he spoke of his process. First, and most importantly, he has to find the right natural woods, usually carting them down from Rurrenabaque or similar small towns in the Amazon basin, 20 hours north of the city.

Then, he begins the month-long process of shaving the wood using traditional tools — edge butt chisels, draw knives, sharpening stones — until a one-peice body is born. This means the neck and chamber of the instrument are not separate pieces glued together, but rather one solid unity of wood, which generally provides a much higher quality instrument with more sustain and sensitivity. Then begins an intensively skillful period of wood inlays, detailing, fretting, and calibration.

The whole process is a spectacle; rarely do we ever see things crafted by hand anymore. We’re used to seeing the final product, to ordering something and finding it on our porch one day. The personal connection between artisan and consumer has dwindled over time, much like the indigenous presence in certain city centers.

Maybe it was the rabies vaccine kicking in, but sitting with Ramiro sent jolts through me. To witness a man build something beautiful from raw materials, using nothing but traditional methods and hand tools instills hope that there will always be a place in the world for true craftsmanship.

Once Ramiro has a finely-tuned, beautiful instrument, he calls his friend from across the city to paint beautiful, traditional Aztec designs on the back, making them each a unique work of art.

I was fortunate to spend four days in Ramiro’s shop, chronicling his creative process, and helping him bend wood with a hand-built steam box.

On my last day, I purchased the ronroco that we built together, and it accompanied me for the rest of my trip, up and over Patagonian mountain passes, in and out of grungy hostel bunks, and under tameless Argentinean skies. It became my best friend, a reliable companion. And every time I glide my fingers across the strings, the instrument comes to life and I hear the streets of La Paz, Boliva ringing and singing and crying as Ramiro quietly crafts miracles from matter. Audio samples of my ronroco:

Claudio Hernandez

San Pedro de Atacama, Chile

Jeweler, Silversmith

Utterly alone, and with only my backpack and a bag of tangerines, I made an impulsive decision to hitchhike up the coast of Chile, from Santiago to San Pedro de Atacama, a small town in the middle of the driest terrain on earth.

After four days of walking 20+ miles, and four nights of sleeping behind soiled gas stations on the Panamerican highway, I began to question my motivation. Luckily, I persisted and arrived in San Pedro on a dusty morning in early October. On my previous trip to San Pedro, I’d met a young artist named Claudio, and I was now back to visit and admire his new work.

Claudio’s studio rests on the outskirts of San Pedro’s center, which is, in it’s own right, tiny to begin with. A 15 minute walk through bleached side streets will take you far from the imitation goods sold in the center, and into a small community of artisan workshops. Various craftsmen make their living here, chiseling stones, knitting beanies, and burning patterns into balsa wood using magnifying glasses.

Peeking into each workshop is a visage into the artist’s little world: there is the shoemaker, knee-deep in a pile of leather; the marble cutter, chipping away at a giant lizard statue; the long-bearded painter, doused with fifty shades of orange.

Claudio’s space, “Resistencia,” exists on the fringe of this annex, and is easy to pass by without assuming anything spectacular is happening inside. But passing by would be a grave mistake. A silversmith and jeweler, Claudio started as a wood sculptor and trained under a well-known artist in the Los Dominicos art district in Santiago. A desire for solitude brought him to the vast Atacama, where he taught himself the traditional methodology of stone cutting, smelting, and inlaying.

On my last visit, I watched him craft a personalized ring for a friend, made of bronze and crisocola. Today, he chips away at a small chunk of onyx and carefully matches the stones together, like puzzle pieces, onto beads of liquid silver.

His art is deeply rooted in Mapuche history and indigenous tradition. He only works with native stones (Chilean turquoise, lapis lazuli, pink coral from the coast), and his silver comes directly from the Atacama mines. His strict dedication to preserving culture gives the work a distinctly Chilean feel: nothing is an imitation, nothing is feigned or reproduced, no corners are cut.

It takes him nearly four hours to complete the bracelet, and we share a beer as the torched silver settles on a crinkled tin sheet. I ask him if he travels, and he tells me that he does not. When I implore, he tells me that his art takes him on a new journey every day, that staying rooted with an open mind can sometimes be the greatest adventure of all.

Sitting here in the small workshop, inhaling the invisible dusts of citrine and white topaz, I feel alive and inspired. In a few days’ time, I’ll be back on the road, aimlessly wandering down lost roads, but Claudio will still be here: chipping away at stones in the Atacama, but lost in a creative world few will ever know.